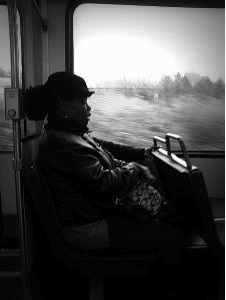

Miss Betty sighed deeply as she navigated her rusty pickup through the stone gates of the mansion. It’s a good thing Alvin wasn’t sitting next to her today, because when his wife sighed like that he liked to watch her rich brown breasts expand out of the neckline of her cotton wash dress and shine like two plump garden aubergines. Then he would reach over and brush her skin with the back of his hand, or perhaps he would grab a breast and squeeze. “Too bad we gots to work today,” he’d say, sparkle in his eyes.

More often that not she’d push him away, concentrating on the cleaning that would need to be done at the rich folks’ summer place, making a mental note of the beds to be changed and the places where she would need to broom out the fine dusting of Bahamian beach sand that might have settled under the bamboo couches and in the corners of the kitchen.

But Alvin wasn’t here today to pester her and cause a ruckus in her determination—Alvin was off in Governors Harbour selling yesterday’s catch to the Roadway Restaurant, a nice mess of grouper, carefully cleaned and iced so they’d be ready for tourist lunches of fried fish with macaroni and cheese on the side. And to tell the truth, Miss Betty didn’t miss him: he was always wanting to do mischief on the big bed or sneak a quick grope in the kitchen pantry and then she’d forget what she was doing Alvin would never get all the windows washed and the light bulbs replaced.

Good to be working alone today, she said to herself, but all the same she felt a little nervous as she pushed open the back door of the silent house. “Peoples just shouldn’t be so rich,” she always thought when she entered the gleaming kitchen with its copper-bottomed pans hanging from the ceiling. Those pans always took her breath away, so different from her two own black iron skillets tucked safely away under the kitchen sink. “Skillets ain’t for decoration. They be for fry-ups and the greasier they is the more they is ready to use,” her mama would say, referring to that same cookware which was now Miss Betty’s most prized possession. “I got plenty of things for my own lifetime, and I ain’t got hardly nothing.”

Miss Betty didn’t expect the two young people to be awake when she arrived: she usually had a good three hours to clean before a dark tousled head appeared and a thick voice wondered if there was coffee and a croissant. Alvin would have taken bets on whether it would be the brother or the sister who straggled down from the upstairs bedrooms—Alvin liked to bet on almost anything, she mused: who would be driving the water truck or whether Barbie’s All You Can Eat would have pineapple duff, or whether it would rain before next Friday. Miss Betty didn’t exactly approve of Alvin’s betting, and she didn’t approve of leaving twenty-year-old twins alone in a winter home in the Bahamas, and she certainly didn’t approve of people who didn’t start their days until almost lunchtime, expecting her to clean up the leftover party from the night before—liquor bottles, pizza crusts, underwear draped over the furniture, broken glass.

She knew enough not to complain—once she had said something to the mother of the twins, staying at the cottage on a rare visit to see her children. “They get crazy sometimes,” the woman had said. “But they’re good kids—they’re just having fun on their vacation. If you can’t do the job….” And her voice had trailed off in an implied consequence.

So Betty kept her thoughts to herself most of the time and just concentrated on her own affairs, which were enough of a burden without adding anyone else’s troubles to her own collection of woes. She needed the job, which was really pretty easy most of the time when the owners we back home in New York someplace, and she knew enough not to let a good thing go when she had it.

Opening the kitchen scullery door, she took out the mop and cleaning bucket, not really thinking about the twins and the mess would find when she went into the living room and out onto the patio. So deep was Miss Betty in her own thoughts that she stumbled and fell heavily against the wall when she tripped over the bloody arm of the body stretched lifelessly across the pink ceramic tiles of the kitchen floor.

Writing Prompt: Patricia Ann McNair